What was the Sipadan-Ligitan dispute about?

Topic of Study [For H2 History Students]:

Paper 2: Regional Conflicts and Co-operation

Source Based Case Study

Theme III Chapter 1: Inter-state tensions and co-operation: Causes of inter-state tensions: historical animosities & political differences

About the Islands: Sipadan and Ligitan

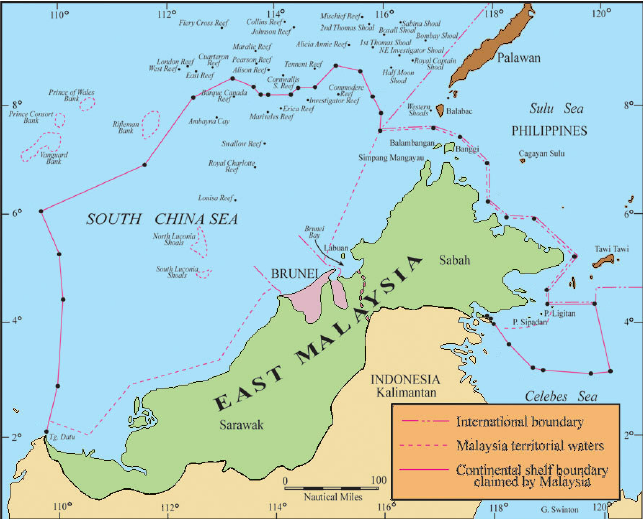

Pulau Sipadan and Pulau Ligitan are located in the northeast coast of Borneo. The surrounding waters of Borneo (which comprises of East Malaysia and Indonesia) are popular scuba diving destinations.

In 1891, Britain and Netherlands signed the Anglo-Dutch Convention, which separated the seas in the North Borneo region into two separate zones. Based on the Convention, Indonesia claimed the two islands.

Formation of the Malaysian Federation (1963)

On 16 September 1963, the Federation of Malaysia was formed. It included the merger with Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak. Malaysia inherited North Borneo from the British. As such, Pulau Sipadan and Pulau Ligitan were part of Malaysian territory.

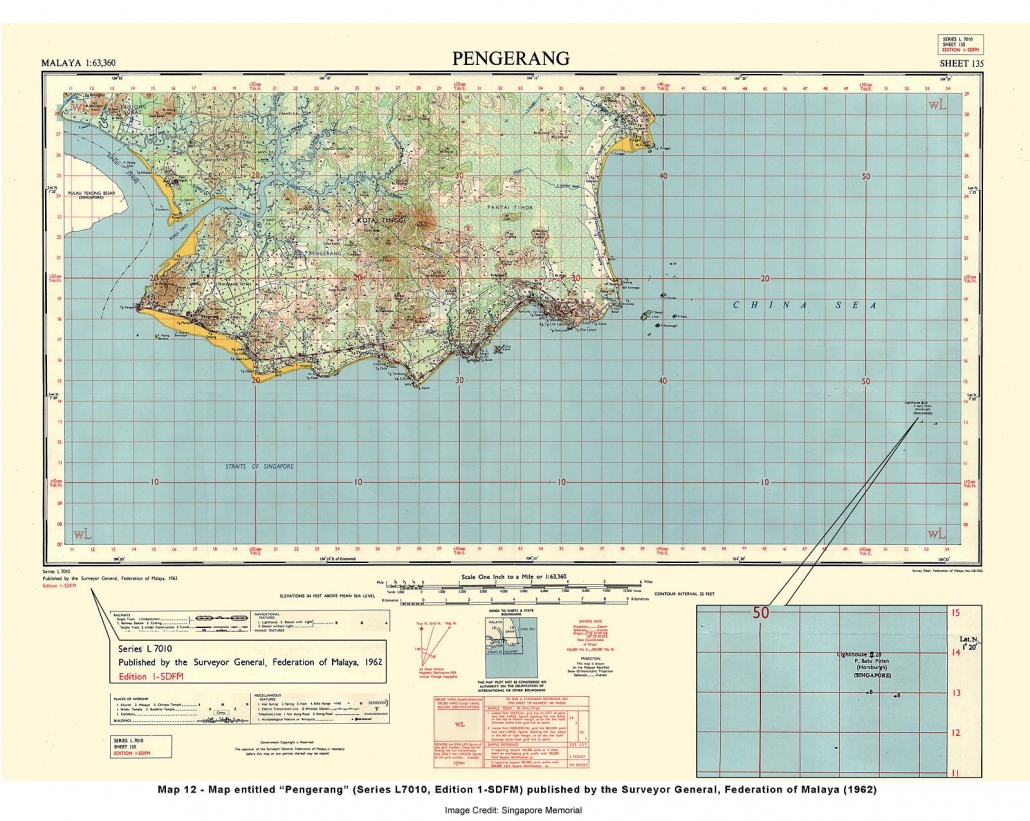

However, inter-state tensions surfaced when Malaysia published a controversial map [the same map that gave rise to the Pedra Branca dispute] on 21 December 1979 that included Sipadan and Ligitan within its territories. In February 1980, Indonesia declared its objection to Malaysia’s map.

Violent Confrontations: Gunboat diplomacy

In 1991, Indonesia discovered the conduct of tourist activities by Malaysia in Pulau Sipadan. The latter allowed a private dive company to build chalets and a pier.

Since Indonesia’s request for Malaysia to halt the commercial development was in vain, the threat of military force was employed against Malaysia. In July, Indonesia seized a Malaysian fishing vessel near Sipadan.

Conflict De-escalation: Negotiations

Fortunately, both parties agreed to resolve the dispute amicably. In October, a Joint Commission Ministerial (JCM) meeting was held. During the formal discussion, Indonesia complied with Malaysia’s request to reduce its military presence. In the process, a Joint Working Group was set up to facilitate the management of this territorial dispute as well as other bilateral issues.

Resolution: The International Court of Justice

The dispute was eventually resolved when Indonesia and Malaysia agreed to submit their case to the Court in 1997. On 17 December 2002, the Court concluded that “sovereignty over Pulau Ligitan and Pulau Sipadan belonged to Malaysia”. Its basis was that Malaysia administered these islands over a considerable period of time and that Indonesia did not protest against these activities then. Both parties then respected the Court’s judgment.

What can we learn from this article?

Consider the following question:

– How far do you agree that historical animosities were the main reason for the inter-state tensions between Indonesia and Malaysia after independence [to be discussed in class]?

Sign up for our JC History Tuition and learn how to consolidate your content effectively. Then, we conduct skills-oriented classes to show you how to apply the information in a structured and clear way. For instance, you will learn how to assess the reliability of sources based on the given factual information that you have seen in the sources as well as from your own knowledge.

The H2 and H1 History Tuition feature online discussion and writing practices to enhance your knowledge application skills. Get useful study notes and clarify your doubts on the subject with the tutor. You can also follow our Telegram Channel to get useful updates.

We have other JC tuition classes, such as JC Math Tuition and JC Chemistry Tuition. For Secondary Tuition, we provide Secondary English Tuition, Secondary Math tuition, Secondary Chemistry Tuition, Social Studies Tuition, Geography, History Tuition and Secondary Economics Tuition. For Primary Tuition, we have Primary English, Math and Science Tuition. Call 9658 5789 to find out more.