What was the Fisheries Jurisdiction case about?

Topic of Study [For H2 History Students]:

Paper 1: Safeguarding International Peace and Security

Section B: Essay Writing

Theme III Chapter 2: Political Effectiveness of the UN in maintaining international peace and security

Dollar and Cents: The Significance of Icelandic Fisheries

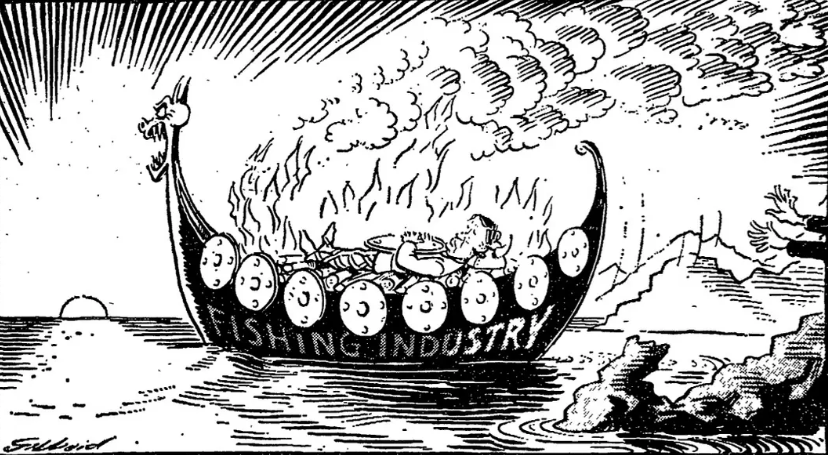

Iceland has one of the richest fishing grounds in the world. The fishing industry is recognised as a key pillar of its economy. It employs nearly 5.3% of its total workforce. It exports a wide range of fish and seafood such as the valuable cod and haddock. Currently, Iceland maintains a 200 nautical miles exclusive fishing zone.

A Fishy Situation: Disputes over the Delineation of Fishing Zones

In 1948, the Icelandic government passed a law to establish conservation zones for fishing. In 1952, a 4-mile zone was drawn. Six years later, a new 12-mile fishery limit was made exclusive for Icelandic fisherman. However, the United Kingdom (UK) rejected the validity of the Icelandic regulations, even though the latter’s fishermen continued to fish within this newly-declared 12-mile limit.

The First Cod War (1958-1961)

Once the newly-introduced Icelandic law came into force on 1 September 1958, the first Cod War began. The British deployed their four warships from the Royal Navy (HMS Eastbourne, HMS Russell, HMS Palliser and HMS Hound) to protect their fishing trawlers. Likewise, Iceland sent eight small coastguard patrol vessels, including the largest frigate known as the Thor.

The furious Icelandic officials threatened to withdraw Iceland’s membership of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) unless mediation was carried out. Eventually, NATO agreed to engage in formal and informal mediations to resolve the matter.

Both the UK and Iceland reached a settlement in the Exchange of Notes (known as the 1961 Agreement) on 8 June 1961. Both parties agreed to a 12-mile fishery zone situated around Iceland.

The United Kingdom Government will no longer object to a twelve-mile fishery zone around Iceland measured from the base lines specified in paragraph 2 below which relate solely to the delimitation of that zone...

The Icelandic Government will not object to vessels registered in the United Kingdom fishing within the outer six miles of the fishery zone…

Exchange of Notes between the United Kingdom and Iceland, 8 June 1961.

The Second Cod War (1972-1973)

Yet, the consensus did not last as Iceland extended its fisheries jurisdiction to a 50-mile zone on 28 November 1971. Iceland claimed that the 1961 agreement was no longer in effect.

Many Western European states opposed Iceland’s extension, but the Icelandic government maintained its position, arguing that the Cod Wars were part of a bigger conflict against ‘imperialism’ and the achievement of economic independence.

On 1 September 1972, the Iceland law was enforced. Many British and West German trawlers continued to fish within the newly-declared zone. This time, the Icelandic Coast Guard ships were armed with trawl wire cutters to undermine non-Icelandic vessels. The second confrontation was tense as British and Icelandic ships rammed each other.

Fortunately, NATO oversaw a series of talks between the UK and Iceland, starting on 16 September 1973. The outcome in Iceland’s favour as the British warships were recalled a month later.

The Court’s ruling: The crystallisation of customary laws

Additionally, the UK filed an application to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on 14 April 1972 to contest Iceland’s unilateral decision to extend the fishing zone. It pointed out to the Court that Iceland’s claim to zone of exclusive fisheries jurisdiction extending to 50 miles contravenes international law.

On 25 July 1974, the Court ruled in favour of the UK. It concluded that Iceland’s extension to a 50-mile zone in 1971 was invalid, given that Iceland could not exclude the UK from the newly-defined areas between the fishery limits decided in the 1961 agreement. Iceland had to adhere to the 12-mile fishery zone jurisdiction.

Also, ICJ advised both parties to undertake negotiations to resolve their differences amicably. For example, the British agreed to limit fishing activities to areas within the designated limit of Iceland.

Subsequently, two concepts were accepted as part of customary law. First, a fishery zone up to a 12-mile limit from the baseline is acceptable. Second, preferential fishing rights should be granted to a coastal state that has special dependence on its coastal fisheries.

The Third Cod War (1975-1976)

Following the third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III) in 1975, the Icelandic government again announced its intentions to extend its fishery limits to 200 nautical miles from its coast. There were several clashes between Icelandic and British ships, including ramming and net cutting incidents.

On 1 June 1976, NATO mediated sessions for the two parties. An agreement was made, in which the UK could keep 24 trawlers within the 200 nautical miles and their catch was capped at 50,000 tons.

What can we learn from this article?

Consider the following question:

– Assess the view that the International Court of Justice was effective in ensuring adherence to the international law [to be discussed in class].

Sign up for our JC History Tuition and learn to apply your knowledge to source-based case study questions (SBCS), including the topic on the ICJ and UN.

The H2 and H1 History Tuition feature online discussion and writing practices to enhance your knowledge application skills. Get useful study notes and clarify your doubts on the subject with the tutor. You can also follow our Telegram Channel to get useful updates.

We have other JC tuition classes, such as JC Math Tuition and JC Chemistry Tuition. For Secondary Tuition, we provide Secondary English Tuition, Secondary Math tuition, Secondary Chemistry Tuition, Social Studies Tuition, Geography, History Tuition and Secondary Economics Tuition. For Primary Tuition, we have Primary English, Math and Science Tuition. Call 9658 5789 to find out more.