How did decolonisation affect the United Nations?

Topic of Study [For H1/H2 History Students]:

Paper 1: Safeguarding International Peace and Security

Section B: Essay Writing

Theme III Chapter 2: Political Effectiveness of the UN in maintaining international peace and security

Historical context

On 14 December 1960, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the “Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples”. In essence, the Declaration advocated the right to self-determination, thereby bringing an end to colonial rule.

Recognizing that the peoples of the world ardently desire the end of colonialism in all its manifestations, […]

2. All peoples have the right to self-determination; by virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

An excerpt taken from the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1514 (XV), 947th plenary meeting, 14 December 1960.

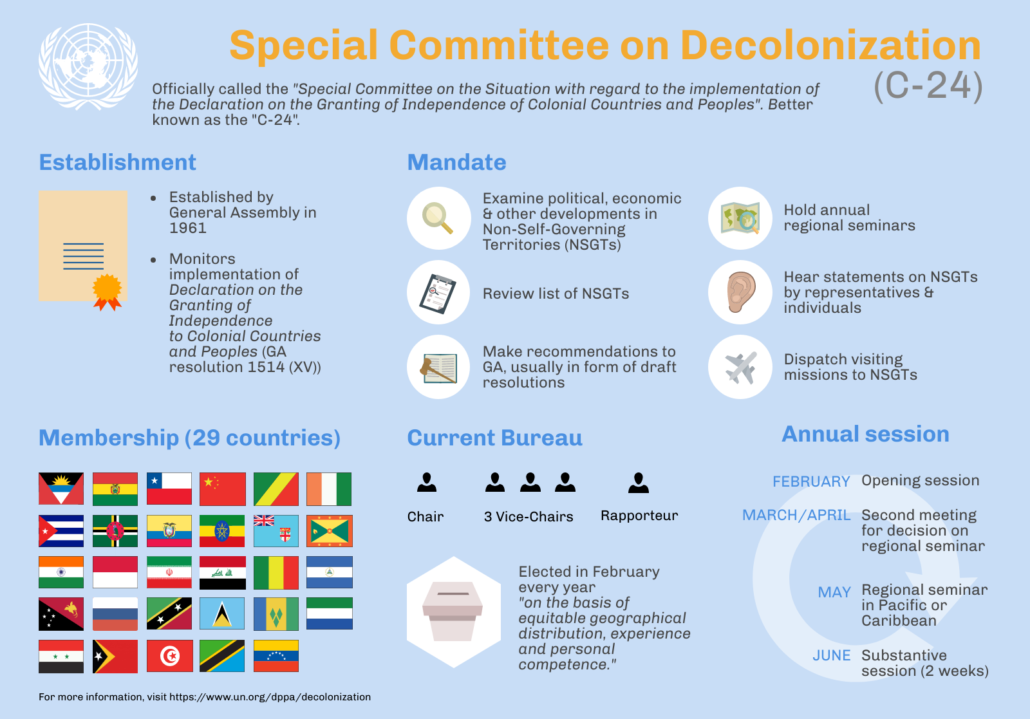

A commitment to decolonisation: C-24

To oversee the decolonisation process, a Special Committee was established in 1961 in accordance to the General Assembly resolution 1654 (XVI). The Committee of Twenty-four, also known as C-24, carries out activities, such as examining the political and economic developments of non-self-governing territories (NSGTs).

Infographic on the Special Committee on Decolonization. [Source: United Nations]

By resolution 1603 (XV) of 20 April 1961, a Sub-Committee on the Situation in Angola was created. Angola was both a colonial issue involving a commencement case, as well as a complex political situation characterized by armed conflict. In 1962 this Sub-Committee was absorbed by what was becoming the main U.N. instrumentality for decolonization, namely the Special Committee of Twenty-Four.

With a view to centralizing the U.N. action in the area of decolonization, and to concentrate it in the hands of the Special Committee of Twenty-Four, the pattern of absorption was repeated with regard to the Committee on South West Africa which was dissolved in 1961.

An excerpt taken from “The United Nations and Decolonization: The Role of Afro-Asia” byy Yassin El-Ayouty.

Branching out to security matters

In the early 1960s, the newly-formed C-24 tried to garner support from the United Nations Security Council. It called on the Council to address the issue in South West Africa, citing security concerns. Likewise, a similar matter was raised in Southern Rhodesia two years later. In 1965, the Committee expressed concerns in the Aden territory, labelling it as a ‘dangerous situation’.

Yet, the Security Council’s responses were not identical. For instance, the Council recognised the threats in South West Africa, but not so in Aden.

It is doubtful if in practice the Committee of Twenty-four had much influence on the policies which the colonial powers pursued in the territories for which they were responsible. Its pronouncements were for them an extremely marginal factor among all the considerations which had to be taken into account (including often a nationalistic home opinion holding diametrically opposite views). They were a factor which, if considered at all, were more important in the eyes of their foreign offices than of their colonial departments which had the main responsibility for policy concerning their colonial territories.

An excerpt taken from “A History of the United Nations: Volume 2: The Age of Decolonization, 1955–1965” by Evan Luard.

What can we learn from this article?

Consider the following question:

– How far do you agree that decolonisation created problems for the United Nations General Assembly?

Join our JC History Tuition to learn more about the United Nations. The H2 and H1 History Tuition feature online discussion and writing practices to enhance your knowledge application skills. Get useful study notes and clarify your doubts on the subject with the tutor. You can also follow our Telegram Channel to get useful updates.

We have other JC tuition classes, such as JC Math Tuition and JC Chemistry Tuition. For Secondary Tuition, we provide Secondary English Tuition, Secondary Math tuition, Secondary Chemistry Tuition, Social Studies Tuition, Geography, History Tuition and Secondary Economics Tuition. For Primary Tuition, we have Primary English, Math and Science Tuition. Call 9658 5789 to find out more.