Sipadan and Ligitan dispute: Revisited

Topic of Study [For H2 History Students]:

Paper 2: Regional Conflicts and Co-operation

Source Based Case Study

Theme III Chapter 1: Inter-state tensions and co-operation: Causes of inter-state tensions

Territorial claims

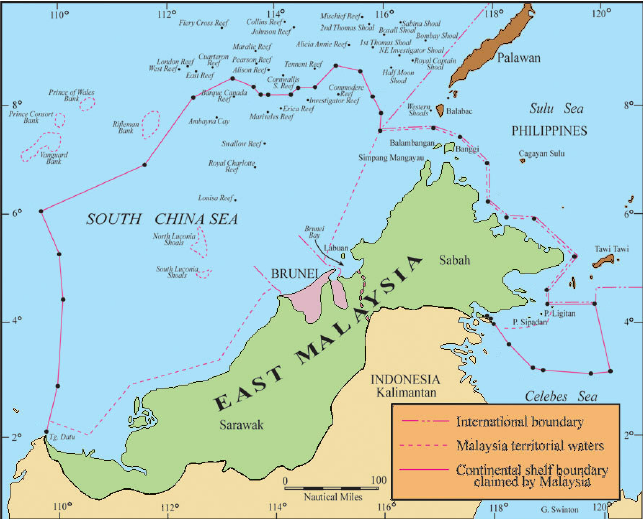

Malaysia and Indonesia had competing claims to the Sipadan and Ligitan islands. These islands were situated in the northeastern coast of Sabah in the Celebes Sea.

Indonesia’s stake was based on the 1891 Anglo-Dutch Convention. Since the two islands were formerly under the Dutch colonial occupation, Indonesia’s attainment of independence had meant that the same islands should belong to them.

In contrast, Malaysia referred to the 1878 Treaty between the Sultan of Sulu and the British North Borneo Company. The British had ceded the North Borneo territory (Sabah) to Malaysia. As such, the two contested islands were under Malaysia’s control.

The former territory of North Borneo was ceded or leased in perpetuity to the British in January 1878 by an agreement signed between the then Sultanate of Sulu and two British commercial agents, namely Alfred Dent and Baron von Overbeck of the British North Borneo Company, in return for payment of 5000 Malayan dollars per year. The sum was increased to 5,300 dollars when the lease was extended to include islands along the coast of North Borneo.

An excerpt from “Sultan of Sulu’s Sabah Claim: A Case of ‘Long-Lost’ Sovereignty?” by Mohd Hazmi bin Mohd Rusli and Muhamad Azim bin Mazlan.

Militarisation of a territorial dispute

The situation appeared tense when both parties turned to their naval forces to address the contestation of islands in the early 1990s.

For example, in 1993, the former Malaysian Armed Forces General, Yaacob Mohd. Zain, that military action was the only answer to unsolved territorial disputes. A typical Indonesian response was an Indonesian naval spokesperson’s announcement that its forces would continue patrolling the islands because they “belong to us and we will defend them.” The crisis reached its peak in 1994 when Malaysian Defence Minister, Najib Tun Razak, visited Sipadan Island. Although the visit did not give rise to any incident, the military situation remained tense. Several subsequent stand-offs between the armed forces of both countries were reported to have taken place in the following years.

An excerpt from “Dispute Resolution through Third Party Mediation: Malaysia and Indonesia” by Asri Salleh.

In July 1982, Malaysia deployed troops to Sipadan and Ligitan islands. Likewise, Indonesian forces have landed in Sipadan island in 1993. Tensions were high when Indonesia accused Malaysia of conducting a military exercise in September 1994 to take over the two islands. In response, Indonesia held a naval exercise, while emphasising that it was not related to that dispute.

In July 1982, Malaysia occupied the two islands to the chagrin of its neighbour. As was the case with Swallow Reef, Malaysia began to develop the island for tourism. By early 1991 Indonesia started to protest the change in the status quo of the islands. Malaysian fishermen came eyeball to eyeball with the Indonesian Navy in July 1991 after which a joint commission was established. Even so, Malaysia claimed that Indonesian armed forces actually landed on Sipadan several times in 1993 and in 1994 the Indonesia Navy staged large-scale exercise involving 40 vessels and 7,000 troops in the vicinity.

An excerpt from “Non-Traditional Security Issues and the South China Sea: Shaping a New Framework for Cooperation” by Shicun Wu and Keyuan Zou.

What can we learn from this article?

Consider the following question:

– How far do you agree that the Sipadan and Ligitan dispute has strained Indonesia-Malaysia relations in the post-independence period?

Join our JC History Tuition to learn more about territorial disputes in the theme of Regional Conflicts and Co-operation. The H2 and H1 History Tuition feature online discussion and writing practices to enhance your knowledge application skills. Get useful study notes and clarify your doubts on the subject with the tutor. You can also follow our Telegram Channel to get useful updates.

We have other JC tuition classes, such as JC Math Tuition and JC Chemistry Tuition. For Secondary Tuition, we provide Secondary English Tuition, Secondary Math tuition, Secondary Chemistry Tuition, Social Studies Tuition, Geography, History Tuition and Secondary Economics Tuition. For Primary Tuition, we have Primary English, Math and Science Tuition. Call 9658 5789 to find out more.