What is the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia?

Topic of Study [For H2 History Students]:

Paper 2: Regional Conflicts and Co-operation

Source Based Case Study

Theme III Chapter 2: ASEAN (Growth and Development of ASEAN: Building regional peace and security)

Topic of Study [For H1 History Students]:

Essay Questions

Theme II Chapter 2: The Cold War and Southeast Asia (1945-1991): ASEAN and the Cold War (ASEAN’s responses to Cold War bipolarity)

The document

On 24 February 1976, the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia (TAC) was signed. This peace treaty was formalised during the Bali Summit in Indonesia by the five founding members of ASEAN.

In their relations with one another, the High Contracting Parties shall be guided by the following fundamental principles :

a. Mutual respect for the independence, sovereignty, equality, territorial integrity and national identity of all nations;

b. The right of every State to lead its national existence free from external interference, subversion or coercion;

c. Non-interference in the internal affairs of one another;

d. Settlement of differences or disputes by peaceful means;

e. Renunciation of the threat or use of force;

f. Effective cooperation among themselves.

An excerpt from the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia, Chapter I: Purpose and Principles, Article 2, 24 February 1976.

Notably, this document was signed a year after the Vietnam War concluded, with the forces in North Vietnam unifying the Vietnam territory under Communist rule. It was an alarming development, considering that ASEAN was futile in keeping the region free from external interference, as seen by its use of the Zone of Peace, Freedom and Neutrality (ZOPFAN) in 1971.

Application: Dispute resolution

To put the principles of the TAC into practice, ASEAN formed a ‘High Council’ that features a judicial dispute-settlement mechanism to resolve regional matters amicably. Yet, the High Council was only being referred to when Indonesia suggested to resolve the territorial dispute with Malaysia with regards to the Sipadan and Ligitan islands. Eventually, when Malaysia objected, this dispute was brought up to a globally-renowned International Court of Justice (ICJ).

The only time that resort to the dispute-settlement provisions of the TAC was ever considered was in the mid-1990s, when Indonesia proposed using the TAC’s High Council to help resolve its dispute with Malaysia over ownership of the Sipadan and Ligitan islands. Malaysia declined the proposal. Instead, Kuala Lumpur preferred, and President Soeharto eventually agreed, to take the dispute to the International Court of Justice in The Hague, which has since ruled in Malaysia’s favour.

An excerpt from “Southeast Asia in Search of an ASEAN Community” by Rodolfo Severino.

Application: Extra-ASEAN engagement

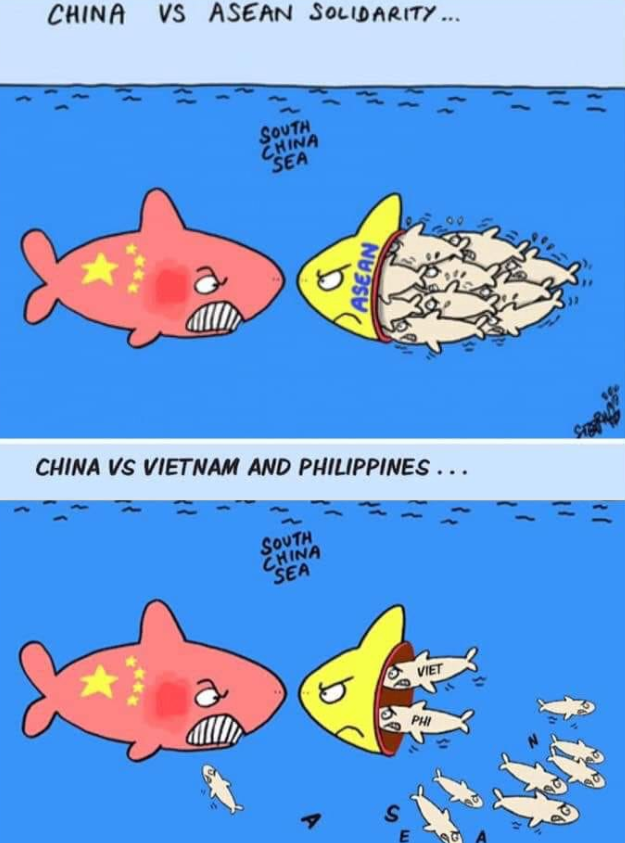

In the post-Cold War phase, ASEAN re-positioned itself to maintain its relevance. The establishment of the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) in 1994 was meant to engage non-ASEAN countries, particularly the big powers like the USA and China, through peaceful talks.

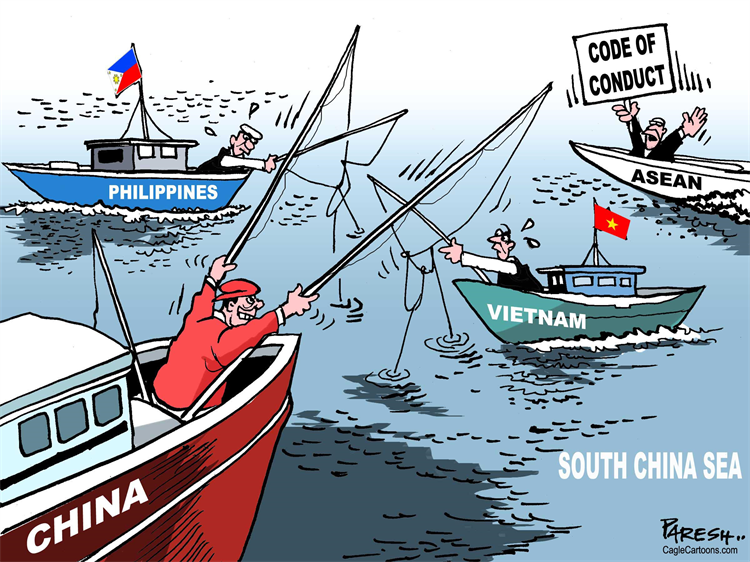

The TAC was applied to enforce the need for proper code of conduct so as to de-escalate tensions and resolve disputes, such as the ongoing territorial clashes in the Spartly Islands.

In the early 1990s, ASEAN supplied an inclusive security dialogue forum to bring together all the major regional powers and players, something other actors were unable to do. Through this process all powers agreed to ASEAN’s TAC as a regional code of conduct, and to dialogue as a key aspect of regional strategic engagement, no mean feat considering the US’ and China’s scepticism and opposition to multilateralism in the initial post-Cold War years.

An excerpt from “Understanding ASEAN’s Role in Asia-Pacific Order” by Robert Yates.

What can we learn from this article?

Consider the following question:

– How far do you agree that the TAC was effectively applied in ASEAN’s response to the Cold War?

Join our JC History Tuition to analyse the political effectiveness of ASEAN in the Cold War and post-Cold War periods. The H2 and H1 History Tuition feature online discussion and writing practices to enhance your knowledge application skills. Get useful study notes and clarify your doubts on the subject with the tutor. You can also follow our Telegram Channel to get useful updates.

We have other JC tuition classes, such as JC Math Tuition and JC Chemistry Tuition. For Secondary Tuition, we provide Secondary English Tuition, Secondary Math tuition, Secondary Chemistry Tuition, Social Studies Tuition, Geography, History Tuition and Secondary Economics Tuition. For Primary Tuition, we have Primary English, Math and Science Tuition. Call 9658 5789 to find out more.