What is the purpose of the ASEAN Free Trade Area?

Topic of Study [For H2 History Students]:

Paper 2: Regional Conflicts and Co-operation

Source Based Case Study

Theme III Chapter 2: ASEAN Growth and Development of ASEAN: Promoting regional economic cooperation

Renewed vigour: The origins of the AFTA

The end of the Cold War marked a turning point for ASEAN. With the re-integration of Europe and the formation of the European Union (EU), coupled with the formalisation of the North American Free Trade Area (NAFTA), ASEAN-6 saw a pressing need to step up its efforts to compete with these regional trading blocs.

The recent initial agreement to create a North American Free Trade Area (NAFTA) has been a cause of concern in ASEAN. The possibility of trade diversion resulting from closure of the North American market has made ASEAN more cognizant of the need for a ballast to overcome the loss of some of the trade with North America. Similarly, growing fears about the creation of a European Economic Area (EEA) have been voiced within ASEAN.

An excerpt taken from “AFTA: The Way Ahead” by Seiji F Naya and Pearl Imada Iboshi.

During the Fourth ASEAN Summit held in Singapore on 27-29 January 1992, the six ASEAN member states signed the Singapore Declaration, which outlined the unified aim of establishing the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA).

Functions of the AFTA & ASEAN Enlargement

The creation of the AFTA was achieved through the Common Effective Preferential Tariff (CEPT) Scheme, in which tariff rates for manufactured and processed agricultural products had to be reduced to 0-5 percent within a fifteen-year time-frame. In particular, the Declaration identified fifteen groups of products to be subjected to the CEPT Scheme, such as cement, fertiliser, electronics and textiles.

For the newer members (Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam, or CMLV), they were given a longer timeframe to implement tariff reductions.

During the 26th ASEAN Economic Ministers’ Meeting on 22-23 September 1994, the timeframe was reduced from fifteen years to ten years, so as to realise the AFTA goals by 2003. In addition, the CEPT scheme was to be applied to all unprocessed agricultural products.

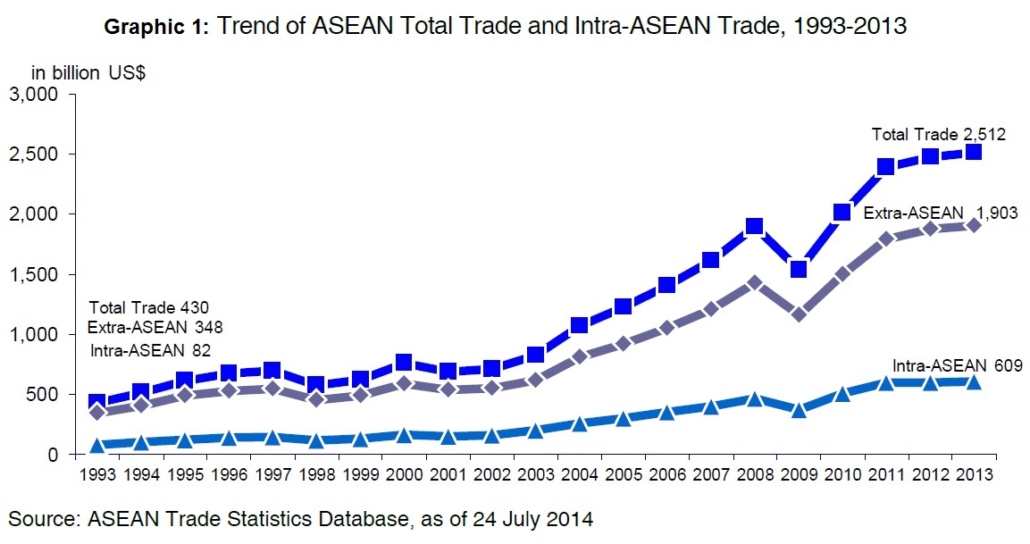

As a result, the value of intra-ASEAN trade rose from less than US$44 billion in 1993 to more than US$85 billion in 1997, suggesting the significant contributions of the AFTA.

Building a resilient regional market: The post-Asian Financial Crisis phase

In spite of the disastrous Asian Financial Crisis (July 1997), the regional association remained undeterred by the economic shocks. During the 6th ASEAN Summit on 15-16 December 1998, the ASEAN-6 members agreed to bring forward the deadline of the AFTA implementation from 2003 to 2002 for items in the Inclusion List. This was known as the Hanoi Declaration.

In 1997, the international financial crisis struck Southeast Asia hard. Immediately, the usual instant commentaries predicted that, as a result of the crisis, ASEAN countries would retreat into isolation, that ASEAN would fall into disarray, that AFTA was dead. Such speculations, some of it evidently arising from herd instinct, were made in defiance of logic and without waiting for the facts to unfold.

[…] The fact was that, in 1998, at their summit in Ha Noi, the ASEAN leaders again advanced the completion date of AFTA, this time by one year, to the beginning of 2002 for the six original signatories to the AFTA Agreement, with the later signatories given a few more years to adjust to regional free trade.

An excerpt taken from a statement by Rodolfo C. Severino, Secretary-General of ASEAN, at the workshop on ‘Beyond AFTA: Facing the Challenge of Closer Economic Integration‘, 2 October 2000.

Join our JC History Tuition to learn more about the ASEAN. The H2 and H1 History Tuition feature online discussion and writing practices to enhance your knowledge application skills. Get useful study notes and clarify your doubts on the subject with the tutor. You can also follow our Telegram Channel to get useful updates.

We have other JC tuition classes, such as JC Math Tuition and JC Chemistry Tuition. For Secondary Tuition, we provide Secondary English Tuition, Secondary Math tuition, Secondary Chemistry Tuition, Social Studies Tuition, Geography, History Tuition and Secondary Economics Tuition. For Primary Tuition, we have Primary English, Math and Science Tuition. Call 9658 5789 to find out more.