How did the UN support decolonisation?

Topic of Study [For H1/H2 History Students]:

Paper 1: Safeguarding International Peace and Security

Section B: Essay Writing

Theme III Chapter 2: Political Effectiveness of the UN in maintaining international peace and security

Historical context

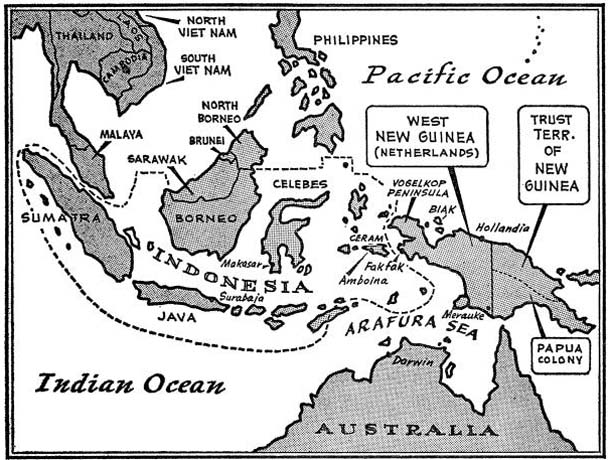

After World War Two, Third World colonies in the Africa and Asia went through decolonisation. However, not all member states of the United Nations were supportive of decolonisation, particularly those that were former colonial powers. In the early 1950s, Indonesia raised its concerns over West Irian, which was still controlled by the Netherlands.

On August 17, 1954, a day chosen with appropriate concern for nationalist symbolism, the Indonesian representative to the United Nations requested the UN Secretary-General to place the West Irian question on the agenda of that year’s regular session of the General Assembly. […] When debate was begun on the issue, Indonesia came forth with ringing declarations of the case against colonial rule.

An excerpt taken from “The Decline of Constitutional Democracy in Indonesia” by Herbert Feith.

Furthermore, the Cold War rivalry has hindered efforts at international cooperation. Although the USA has always been a strong advocate of decolonisation, its British ally convinced it not to express support for this process in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA).

Resolution 1514

During the fifteenth session of the UNGA, member states were called upon to vote for the independence of countries and end of colonial rule. Notably, the USA abstained, whereas the Soviet Union supported the draft resolution. In total, 89 voted for the resolution, whereas 9 abstained.

As a result, UNGA Resolution 1514 (XV) was passed, which was known as the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples.

2. All peoples have the right to self-determination; by virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

[…] 5. Immediate steps shall be taken, in Trust and Non-Self-Governing Territories or all other territories which have not yet attained independence, to transfer all powers to the peoples of those territories, without any conditions or reservations, in accordance with their freely expressed will and desire, without any distinction as to race, creed or colour, in order to enable them to enjoy complete independence and freedom.

An excerpt taken from General Assembly Resolution 1514 (XV), 14 December 1960.

What can we learn from this article?

Consider the following question:

– In view of Third World decolonisation, assess the challenges to the political effectiveness of the United Nations General Assembly.

Join our JC History Tuition to learn more about the United Nations. The H2 and H1 History Tuition feature online discussion and writing practices to enhance your knowledge application skills. Get useful study notes and clarify your doubts on the subject with the tutor. You can also follow our Telegram Channel to get useful updates.

We have other JC tuition classes, such as JC Math Tuition and JC Chemistry Tuition. For Secondary Tuition, we provide Secondary English Tuition, Secondary Math tuition, Secondary Chemistry Tuition, Social Studies Tuition, Geography, History Tuition and Secondary Economics Tuition. For Primary Tuition, we have Primary English, Math and Science Tuition. Call 9658 5789 to find out more.